On 12 September 1962, John F. Kennedy gave a speech at Rice University in Texas that would put the United States on a path toward the Moon before the end of the decade. He explained that the challenge would serve to organize and measure the best of the country’s energies and skills. On 20 July 1969, with just over five months to spare, Neil Armstrong became the first human being to set foot on the Moon, a moment that continues to inspire engineers and explorers alike.

On 23 March 2023, a High-Level Advisory Group commissioned by ESA to explore the importance of human and robotic space exploration for Europe sought to set an equally ambitious goal. In fact, it was practically exactly the same goal that JFK had set out over 60 years before it. The group challenged ESA to propose a scenario for an independent and sustainable European human landing on the Moon within ten years. The report quite harshly stated that “Europe’s lack of ambition stands in isolation” next to the likes of the US, China, Russia, and India. It stated that “for Europe to become a transformative player able to make a difference, truly grand goals and narratives are required.” And what grander goal than challenging the continent to put European boots on the Moon within ten years?

“12-strong star-studded group”

ESA formed the advisory group in July 2022. The purpose of the group was to provide the agency’s decision-makers with an independent and objective high-level assessment of the geopolitical, economic, and societal relevance of human and robotic space exploration and recommend options for a way forward.

The advisory group members were an interesting selection of people. There were a few that you would expect including the chairs of the ESA Council, the European Science Foundation’s European Space Sciences Committee, and the European Inter-Parliamentary Space Conference. There was also a large institutional presence that included a former NATO secretary general, the managing director of the World Economic Forum, and a former Italian minister of Education, University, and Research. And then there were some interesting inclusions. Erling Kagge is an explorer that was the first person to reach the North Pole, the South Pole, and Mount Everest all on foot, Tomasz Rożek is a science communicator, and François Schuiten is a best-selling comic book artist. There was a notable lack of anyone who has any direct experience with human spaceflight. However, over three three-day meetings between September 2022 and January 2023, several experts shared their experience, views, and expertise with the group.

The experts included four European astronauts, multiple directors of foundations, institutes, and councils, a space company CEO, the founder of a creative studio, and a former prime minister of Luxembourg. There were, however, no representatives from companies that are currently developing elements of human spaceflight systems like Airbus or Thales Alenia Space. One could argue that Hélène Huby from The Exploration Company fits into that category however, I still find the lack of participation of this side of the industry in the advisory group or among the experts who spoke to them a little strange. There seems to have been a focus on messaging rather than technical realities.

Interestingly, ESA director general Josef Aschbacher initially shared this concern. “I was a little worried at the beginning because they are not space experts,” said the ESA DG during a briefing revealing the advisory group’s recommendations. However, Aschbacher was nonetheless pleased with the report that the 12-person group produced.

Everything but the kitchen sink

A Moon mission was definitely the headline goal proposed by the advisory group, but it was by no means the only one. The group recommended developing a European commercial LEO space station, cargo and crew capabilities for the Gateway space station, and a sustained presence on the lunar surface. The report loosely connects the development of this infrastructure to what may be the group’s most ambitious recommendation: securing one-third of the future €1 trillion space economy. I keep hearing that number and with the publishing of this report, I was finally curious enough to go looking for its source.

The report references the figure having been sourced from a July 2020 Morgan Stanley report entitled Space: Investing in the Final Frontier. The report highlights the potential impact of declining launch costs driven by reusable launch vehicles. Interestingly, the Morgan Stanley report states the figure in dollars while the advisory group’s report has the figure in euros. I’m not sure this one-to-one conversion is appropriate. The Morgan Stanley report also refers to “manned flight” despite the terminology having been dropped by just about every major space agency years before its publication in favor of crewed or human spaceflight. I’m not saying this is an indication of the quality of the report, but it does hint at a certain level of detachment from the industry it is supposed to be forecasting.

Once I’d dug down into the makeup of that projected $1 trillion by 2040 figure, I found that it had little to do with crewed spaceflight capabilities or robotic exploration. Morgan Stanley looked at industry segments like consumer TV, ground equipment, satellite manufacturing, satellite launch capabilities, Earth observation, satellite internet, and second order impacts (which are defined as indirect impacts that may result from changes to supply, demand, or market conditions. For example, if more rockets are being reused, then demand for the raw materials that are used to build rockets from scratch will be reduced). The forecast does include a category for “non-satellite industry” revenue which may include crewed or robotic exploration. This is, however, a small fraction of the $1 trillion market projection.

That’s not to say that I think Europe shouldn’t strive to claim one-third of the entire space economy, although I think that’s improbable. I do, however, question this goal’s place in a report that is supposed to advocate for the virtues of robotic and crewed space exploration.

There is, however, a more recent report that may have been a more appropriate reference for the advisory group. In May 2022, Citi released a report entitled Space: The Dawn of a New Age. The report detailed the bank’s GPS group’s projections for the commercial space economy and wouldn’t you know it, they also projected that the sector will generate $1 trillion in annual sales by 2040.

What makes the Citi report a more relevant reference is the fact that it details the potential for growth in new industries that could account for $100 billion of that $1 trillion projection. The new industries outlined in the report include commercial space stations, space-based solar power, space exploration, Moon and asteroid mining, space logistics, space tourism, and microgravity R&D and engineering. I think for this particular report, aiming to capture a third of that $100 billion projection would have been a more appropriate recommendation. I still think it’s improbable, though. That, however, doesn’t mean that I don’t believe that Europe, with the right incentive, can’t capture a significant share of that market and I do think this is a goal worth pursuing.

A page from the NASA playbook

Another of the more significant recommendations from the advisory group is for the adoption of “a commercially-oriented procurement policy.” This is a policy that many, including myself, have been advocating for ESA to adopt for several years. It would see ESA and other public institutions define the requirements for large-scale infrastructure or missions and encourage the private sector through funding or guaranteed contracts to propose the most innovative and cost-efficient solution. The public agency would then become an anchor customer buying a service or product. This approach was, of course, so effectively utilized by NASA for its commercial crew and commercial cargo programmes, or was it?

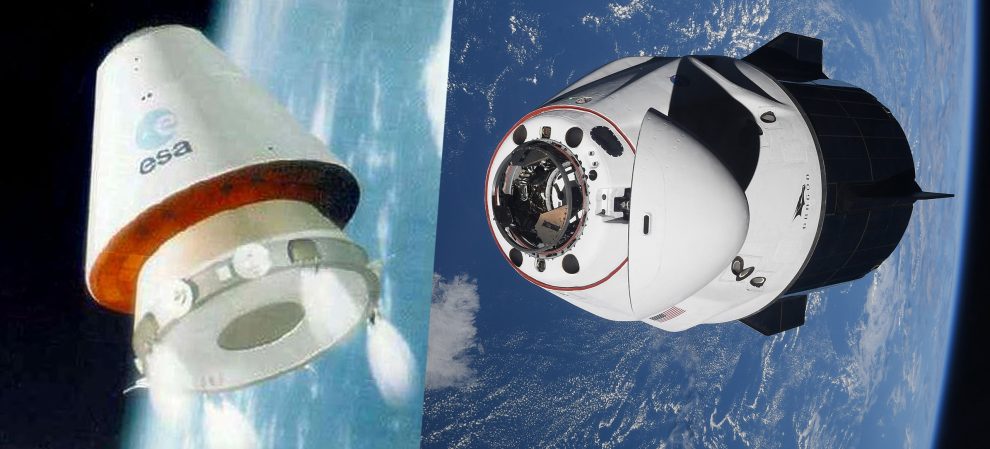

Yes, the programmes did see the development of Cygnus, Cargo Dragon, Crew Dragon, and Starliner (hopefully). The problem is that we see the success of SpaceX as replicable, and I’m not so sure it is. SpaceX is a once-in-a-generation company in the same vein as Microsoft, Apple, and Amazon. They appeared at a time when the market was in desperate need of disruption and completely upended the status quo. The problem is that to replicate the success of those companies you can’t aim for the new status quo but rather beyond it. And that’s assuming that Europe could even replicate the conditions that forged SpaceX. This would require significant public and private funding and a team of wildly talented engineers willing to risk just about everything with the goal of forging a new path for the industry. It would also require a willingness to accept the risk of awarding significant levels of public and private funding to enterprises that may or may not be able to deliver on their promises. I don’t see Europe being able to do this, definitely not in the short to medium term.

It’s natural to try and replicate the successes of others regardless of how different your situation is. I don’t blame the advisory group’s desire to adopt the bases of what became a hugely successful programme for NASA. It was an approach that I too advocated for without giving it the scrutiny that it required. As Europe forges a path towards a crewed launch capability, replicating what the significantly better-funded agency across the ocean has done in the past may not be the best approach. I do, however, think that competition that underpins this kind of approach will be important and that enabling that competition will require ESA to rework many of its governing policies, including but not limited to its geo-return framework (which DG Aschbacher has recently advocated for) and its reliance on entrenched industry monopolies like Arianespace.

A European Moon mission in 10 years: ambitious or delusional?

The advisory group’s report was a little vague regarding exactly what it meant by developing a scenario for an independent and sustainable European human landing on the Moon within ten years. Did the group mean ten years from today? Or did they mean within ten years once the continent has already developed a base-level crewed launch capability? Regardless of the specifics, I don’t see any conceivable way for Europe to put boots on the Moon within ten years.

To achieve this goal, Europe would need to double, or better yet, triple its contributions to ESA, and completely upend the structural bureaucracy that is all but inevitable when 22 sovereign states cooperate towards a single goal. Even then, I think the timeframe would be ambitious. As I can pretty confidently say that neither of those conditions will be met, it’s certainly not unfair to say that Europe cannot put boots on the Moon in ten years. And that’s really not an indictment on Europe. Even the significantly better-funded NASA has been unable to get boots on the lunar surface within ten years. It’s an incredibly difficult task.

Now, a rebuttal to my argument may be that it’s not meant to be a realistic goal but rather an inspirational one. I, personally, don’t find unachievable goals to be inspirational. Ambitious goals, sure. Unachievable goals, not even a little bit.

What I was personally looking for from the advisory group’s recommendations was the development of a crewed launch capability to service low Earth orbit before the end of the decade. To do this, the group should have recommended leaning on existing architecture, which in fairness it did. This would mean utilizing elements like the European Service Module that has been developed by Airbus for NASA’s Orion capsule and maybe even ESA’s uncrewed reusable Space Rider spacecraft currently under development. Here’s where I would have gone a step further than the advisory group’s recommendations, though. I would have recommended developing a crewed launch programme in the same vein as the BEA Multirole Capsule from the 1980s. This approach was not meant to be ambitious. Instead, it was designed to be a stepping stone that could be achieved relatively quickly and within the limits of fairly modest budget increases. This approach focuses on getting something into the air as quickly and cheaply as possible, thus shaking off the disappointment of Hermes and galvanizing a disenchanted European populace with views of their brothers and sisters in space aboard a Europe spacecraft.

I think this group underestimated how inspiring it was for the average US citizen to see Bob and Doug step out of the long shadow of the Space Shuttle aboard the Crew Dragon Endeavour. Hell, it inspired me far more than the uncrewed Artemis 1 mission. Interestingly, the group’s own report seems to show that I am not alone in this belief.

In a table that tracks the global reach of ESA communication for four different events, the new ESA astronaut class announcement in 2022 topped the list with 1.6 billion views. Artemis 1, on the other hand, managed 1 billion views. The simple fact is that Europeans want to see other Europeans in space launched from European soil aboard European launch vehicles, to paraphrase former NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine

Conclusion

There hasn’t yet been a flood of news coverage of the advisory group’s recommendations. The three most prominent responses I have found came from Politico, BBC, and SpaceNews. The Politico article was titled “Europe told to aim for a moon mission” and the BBC piece mentions the recommendation to pursue a European crewed Moon mission within 10 years in the third sentence before any of the advisory group’s other recommendations. The SpaceNews story is, unsurprisingly, far less sensational, focusing on a recommendation for “a comprehensive human spaceflight program” rather than the Moonshot goal. The problem is that SpaceNews is targeted far more to an industry audience whereas Politico and BBC are more likely to be consumed by the general public. As a result, the most likely takeaway the average European will get from the reporting on the advisory group’s recommendations is that Europe and ESA have been advised to go to the Moon within 10 years. Again, with such a focus on assembling a group that specialises in messaging, it frustrates me that they didn’t see this coming. The problem, as I have already discussed, is that no one really believes this is possible.

When JFK announced the United States’ intention to go to the Moon before the end of the 1960s, the average American believed that reaching the Moon before the USSR was practically a matter of life and death. This allowed the country to mobilize the support, expertise, and, most importantly, the necessary funding to achieve something that appeared impossible. Europe doesn’t have that kind of existential motivation and even if it did, you would have to assume that the continent was a monolith. The reality is that each of ESA’s 22 member states has its own goals and preferred outcomes and its own reasons for choosing to fund or not fund particular programmes.

The messaging should have been far simpler: We believe that Europe should develop crewed launch capabilities for these reasons. With crewed launch capabilities, you unlock everything else. It is the pivot point for commercial space stations, Moon missions, and ambitious expeditions into deep space. With a simplified message, headlines don’t report the impossible but rather an ambitious new direction.

What’s next? An ESA council working group has been set up to review the recommendations of the 12-person advisory group. This working group will prepare for discussions on the topic at the agency’s next Space Summit which will be held in Sevilla, Spain on 6 November 2023. However, a decision to fund the development of a crewed launch capability will have to wait until the next ministerial level council meeting, which will likely be held in 2025.

Add Comment